Carter's Grove Historical Report, Block 50 Building 3Originally entitled: "Opportunities for l7th-Century Interpretation at Carter's Grove"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series—1645

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1994

OPPORTUNITIES FOR

17TH-CENTURY INTERPRETATION

AT CARTER'S GROVE

OCTOBER 21, 1977

(Expanded

November 10, 1977)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| On-Site Reconstructions | 3 |

| On-Site Identification | 3 |

| THE MARTIN'S HUNDRED MUSEUM | 4 |

| The Location | 5 |

| Content of the Museum | 6 |

| The Building | 11 |

| Funding | 13 |

| Appendix: Budget Analysis | 15 |

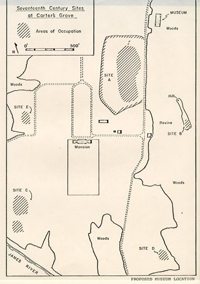

| Figure 1Carter's Grove Site Plan | Following p.1 |

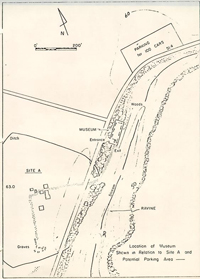

| Figure 2Location of Museum | " " p.5 |

| Figure 3Provisional Plan for Display Layout | Rear pocket |

To: Mr. C. H. Humelsine

From: I. Noël Hume

Re: Opportunities for 17th-century Interpretation at Carter's Grove

Archaeological excavations at Carter's Grove in 1976 and 1977 have not only carried the interpretable history of the land back to 1619, but have added a new chapter to the story of colonization in North America.

Such expansive claims are more easily accepted when one realizes that very little is known about the social history of Virginia in the second quarter of the 17th century. It was, nevertheless, an era of tremendous importance in that it not only covered the political changes and uncertainties generated by the collapse of the Virginia Company and the English civil war; it also embraced the formulative years wherein Virginia's settlers laid the foundation for the plantation economy that was to control the Commonwealth's development at least as late as the mid 19th century. I have dubbed this period "Predynastic Virginia," the years before the rise of the handful of great landowning families who dominated the Virginia scene from the early 18th century onward.

Carter's Grove is uniquely suited to telling the story of the development of plantation life, not only in the 18th century, but through three centuries. By sheer good fortune it seems that the surviving 790 acres around the mansion were at the heart of the land's European development from the time that it was established as Martin's Hundred in 1619 (on a 1,500 acre tract) through to the present day. The Martin's Hundred Society, which was incorporated in 1618 as a secondary private company with a charter from the Virginia Company of London, created a colony within the colony, and it is the archaeological remains of this enterprise, and its immediate successors, that have been revealed during the past two years' digging.

The considerable degree of autonomy granted to the proprietor of the Martin's Hundred Society, made their Virginia settlement separate from, and yet a parallel to the master enterprise at Jamestown. Thus, the discovery of the fort at Carter's Grove and the realization that its character closely matches the only extant description of the Jamestown fort, serves to highlight this comparison. After Virginia became a crown colony in 1625, Martin's Hundred lost much of its identity and became no more than a James City County parish. Because the county court records were burned during the American Civil War, we know little or

17th Century at Carter's Grove

17th Century at Carter's Grove

Areas of Occupation

2

nothing about the population of Martin's Hundred Parish in the second half of the 17th century, and the excavations have been equally uninformative on that score. All the sites so far explored were abandoned by about 1645—for reasons yet to be explained. In spite of finding twenty-three graves at the site dug in 1976 (Site "A"), the fate of the Martin's Hundred colonists remains as much a mystery as the disappearance of Sir Walter Raleigh's "Lost Colony." On the credit side, however, much has been learned about the Martin's Hundred settlement in the 1620s.

Just as Williamsburg has long needed a Carter's Grove to help interpret the city's role in the life of 18th-century Virginia, so the interpretation of Jamestown has lacked an opportunity to tell the story of the development of the colony around and away from it. Instead, most visitors think of Jamestown as being all there was to Virginia in the 17th century. In reality, apart from being the administrative center, Jamestown was a totally consumer oriented community which could not have survived without the people who left it to build the colony's economy in the fields and woods from Elizabeth City to Richmond. This, however, is a story that can be told at Carter's Grove, for the settlement at Martin's Hundred was both administrative and productive.

Although doubt remains as to whether there was ever a properly laid out town at Martin's Hundred in the style of Jamestown, it existed at least in name. Wolstenholme Towne may have been no more than a church on the land assigned to Martin's Hundred's semi-official "governor" William Harwood. Current thinking has it that Harwood was the probable builder of the fort, in which case, what there was of Wolstenholme Towne may have been confined within the palisade or have been laid out between fort and river.

History tends to be dull if nothing dramatic happens, and we are fortunate at Carter's Grove (nee Martin's Hundred) in that it was the principle victim of the Indian massacre of 1622. Thus, from an interpretive point of view, the massacre serves to bring the Indians into the picture while dramatizing the role of the fort and its arms and armor. Additional dramatic highlights are provided by the plague which raged through the colony in 1623 killing at least twenty-eight in Martin's Hundred. These major events, coupled with many moments of individual drama (as revealed through the Virginia Company Records), ensure that any interpretation of Martin's Hundred can focus on people as well as on excavated things.

Two sites have been studied in their entirety (Sites "A" and "B"), and a third, the fort area, has been partially explored (see Fig. 1). At least two more sites remain to be excavated to the east of the mansion in the vicinity of Grice's Run, while there is one, perhaps more, still to be investigated to the west of the house. In addition, there is an Indian ossuary (cemetery) to be examined west of the Burwell graves. Although 3 all the remaining sites cannot hope to be explored as part of the present archaeological campaign at Carter's Grove, their presence ensures that any archaeological interpretation can be augmented by fresh discoveries (and continuing press and public interest) for a long time to come.

The Commonwealth's archaeological sites are pages of Virginia history, and it is no overstatement to insist that if we destroy them by excavation (for all excavation is destructive) and fail to publish what we have learned, we are no better than looters. The immediate question, therefore, is how do we "publish" what has been found at Carter's Grove? How do we get the story across to the American public in a way that is as entertaining and exciting as it is instructive? In arriving at the answer, we must take into consideration several other criteria. Whatever we do must: a) be an economic as well as a cultural asset to C.W.; b) operate with minimal staff and low maintenance; c) be compatible with whatever development plans C.W. may have to tell the l8th- and 19th-century stories of plantation life, and d) be sufficiently extensive and time consuming to appreciably extend the visitors' stay at Carter's Grove.

The following proposal addresses itself to these needs, reviewing several seemingly attractive options which do not measure up to the requirements before focusing on the one that does.

On-Site Reconstructions

Although we have found a group of nine structural locations on Site "A," the site of another house on Site "B," and will eventually uncover the complete ground plan of the fort (Site "C") plus whatever buildings may have stood inside it, we have insufficient evidence to reconstruct anything with the accuracy expected of C.W. Nevertheless, it is highly desirable that the public sees something on the ground, and be able to stand where the early colonists stood and lived.

On-Site Identification

The physical identification of archaeological features can be an effective addition to a conventional museum-style presentation, but it can never be a satisfactory substitute. The combination of visitor center and walking tour of the house locations at Jamestown well demonstrates how the two can be used together—though the new center is a classic example of how not to present the archaeology and history. Like roadside historical markers, site identification can be of interest to passing visitors, but passing is the key word. The marked layout of a house site (an outline of short posts or horizontal logs, surrounding an area of marl or gravel) is not worth trekking to, if that is all there is to see. Coupled with a nature walk or en route to another exhibit, it can be worthwhile.

4The Martin's Hundred fort is an obvious candidate for on-site identification, but I do not believe that it would be worth its upkeep.

- 1The site is extremely poorly drained, water lying there through much of the year.

- 2The location is extremely hot in summer—and unapproachable in wet weather.

- 3The fort's relationship to the river and to Jamestown Island is better seen from the ridge beside the mansion than it is on the site itself.

- 4Unless it is worked into some kind of walking tour of the plantation, the fort is on the way to nowhere.

- 5Its location threatens a visual conflict with the interpretation of the 18th century at Carter's Grove.

For these reasons, I feel that the fort site is best recalled by means of a low, illustrated and descriptive panel on the bluff southwest of the mansion.

The single house location (Site "B"), though a source of fine and evocative artifacts, is itself very uninteresting, and, like the fort, is on the way to nowhere—unless it is incorporated into a woodland nature trail.

This leaves only Site "A," which, fortunately, has several advantages. With its nine structures, fenced enclosures, and scattered cemetery, it is both varied and large enough to absorb a considerable number of visitors. The site also has a stretch of l7th-century roadway (between buildings and cemetery) and therefore is spread over a large enough area to make walking part of the on-site activity. In short, it cannot be absorbed at a glance. By itself, Site "A" can only come alive if its historical and archaeological story are told by a guide. Signs are not enough either to instruct or to detain the visitors long enough to make a major addition to their stay at Carter's Grove. Coupled with a museum style exhibit, however, Site "A" can do its job with no more than a few "reminder" panels to keep the visitor in mental touch with what he has previously been shown.

THE MARTIN'S HUNDRED MUSEUM

I am aware that we are chary about describing an archaeological exhibit or display at Carter's Grove as a museum, but a good case can be made for doing so. It is my conviction that we now have two stories to tell: the 18th-century narrative which begins with Robert Carter's naming the land "Carter's Grove," and the much earlier story of Martin's Hundred. Both should be clearly and proudly defined, and, as the l8th-century story is to be told in the original mansion, identifying the older narrative 5 as being unfolded in a museum seems both logical and desirable. If one wishes to soften the word and give it a truly l7th-century ring, one might write it as a Musaeum recalling that Virginia visitor John Tradescant (he was here in 1642 and 1654) formed the first British museum, the Musaeum Tradescantianum. But that is a detail. What I am proposing is an exciting and modern museum devoted entirely to the story of 17th-century life at Martin's Hundred and linked geographically to an on-the-ground presentation of the Site "A" settlement.

The Location

Carried away by the natural beauty of Site "B," I had long favored that as an ideal location. It could make use of the woodland as part of the exhibit, and it was out of sight from the mansion and therefore would not intrude on the 18th-century story. It was also a quarter of a mile walk from the mansion (half a mile round trip), needing a ravine-spanning bridge to reach it, as well as some high maintenance, rustic roadway. In inclement weather, it would attract no visitors at all, and even in summer many elderly people would balk at a trek through the woods. Nevertheless, the woodland east of the mansion offers an important asset, namely concealment from the mansion.

The location shown on the drawing (Fig.1) has the advantage both of concealment and proximity to Carter's Grove's main centers of interest. It is reached by existing roads and passed by the main utility lines running to the mansion. It is also adjacent to Site "A." It is important also to note that the edge of the woods angles immediately north of the proposed museum location enabling a parking area to be added out of sight either from the mansion or Site "A."

In the absence of a fully developed master plan for the interpretation of the 18th-century plantation, it is impossible to accurately determine walking distances between key points of interest and any new reception and parking area associated with the Country Road. Similarly, there being no decision as to how people are to move about the plantation, one can now only state that the museum location is in reasonable walking proximity to the mansion along a path that would make use of the Site "A" road.

Site "A" is located unbecomingly close to the present parking area which is, in any case, an unattractive intrusion into the colonial scene. One hopes, therefore, that the latter will eventually be moved to a less central location, one that might be to the advantage of the Martin's Hundred Museum, alleviating the need for the parking facility discussed above. One more point should be made about Site "A" as an on-the-ground exhibit: Its fences can be reconstructed, and the area defined, without any imposition on the mansion's l8th-century sight lines.

Location of Museum

Location of Museum

Shown in Relation to Site A and Potential Parking Area

Content of the Museum (Figure 3)

Before discussing the kind of building envisaged, it is necessary to outline the range of potential exhibits and the rationale for their inclusion.

- 1

Foyer capable of accepting 35 people and containing a reception desk and a model of the Carter's Grove tract showing the location of the l7th-century sites in relation to the river and the mansion.

The foyer's rather large size is based on experience at the James Anderson House which has taught that it is difficult to absorb groups if they can only be fed into the building a handful at a time. This is particularly true in bad weather.

- 2

A small exhibit devoted to the Indians who lived on the Carter's Grove acres for thousands of years before the advent of the white man and who represented the principle threat to his survival once he arrived. Greatest emphasis would be placed on the Indians in what is called the "Contact Period," for it was these who so dramatically affected the development of the colony and of Martin's Hundred.

A small number of Indian artifacts have been found in the excavations. These would be augmented with enlargements of the John White drawings, and with reproductions of Virginia Indian arrows and other artifacts taken back to England by John Tradescant and which are now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.

- 3The next exhibit sets the archaeological scene and tells how the search for evidence of Carter's Grove in the 18th century unexpectedly opened a door to the previous century. The exhibit will show photographs of the Martin's Hundred excavations, and demonstrate how the ground's stratigraphy helps the archaeologist chronicle the past. It will also show how post holes are dated by artifacts found in them, and demonstrate what is to be learned from the contents of trash pits, wells, etc.

- 4

The general archaeological introduction now becomes more specific and focuses on the excavation of Site "A's" colonial cemetery to show what evidence we have to reveal how and when those people may have died. This enables the first taste of the Martin's Hundred history to be established, namely the massacre of 1622 and the plague of the following year.

The concept of beginning with death and moving backward into life may at first seem an unusual approach; nevertheless, it is invariably the archaeological way of 7 doing things. In this instance, however, it also has the advantage of keeping the Indians in mind, and it has a dramatic impact not to be found in the archaeological evidences of the drudgery of day-to-day living. One hopes, nonetheless, that thinking about death in Martin's Hundred will prompt the visitor to ask about life. Who were these people? Where did they come from?

- 5The next exhibit is designed to answer some of those questions. Using back-lit photographic transparencies of details from contemporary genre paintings, the visitor looks at the faces of people who are alive in the second quarter of the 17th century, people drawn from both high and low estates: tavern topers and whores, rustics, housewives, and the lesser landed gentry. It is here that we summarize the establishment of the Virginia Colony and the founding of Martin's Hundred. The emphasis remains on people, on emigrants and the notion that America has always been a melting pot: English, French, Walloons, Dutch, Germans and Italians.

- 6We turn now to the new arrivals' protection against their enemies. The display features a conjectural model of the Martin's Hundred fort, and recalls the colonists' fear of both the Indians and the Spaniards. The fort brings us easily to personal protection: arms and armor.

- 7This exhibit shows the kinds of weapons and armor used and worn by the Martin's Hundred settlers and features archaeologically recovered weapon fragments and the complete arms of which they were part. The same treatment is devoted to armor, and includes both plate armor and chain mail (examples of which we now have). Captions include quotations from contemporary sources describing the problems inherent in wearing European armor and employing medieval tactics while fighting a modern guerrilla war with the elusive Indians.

- 8The Carter's Grove (Martin's Hundred) helmet is featured, and here we return to the concepts of archaeological research, illustrating how the helmet (the first of its kind ever found in America) was brought out of the ground and restored in the laboratory.

- 9A display to illustrate the role played by the Tower of London in supplying the Virginia Company with arms and armor after the 1622 massacre. The exhibit will feature several items to be put on loan to us by the Tower Armouries illustrating the range of arms sent here in the 17th century.

- 8

- 10Having examined the military aspects of life in Martin's Hundred we turn now to domestic life. That, of course, begins with houses. The display shows pictures of the post hole patterns revealed in the excavations, models or drawings of possible reconstructions, and details from contemporary Flemish paintings depicting comparable houses (e.g. paintings by Breugel and Siberecht). Archaeological evidence is provided by part of an original post, window glass, window lead, delftware fireplace tile, roofing tile and bricks.

- 11Household interiors follow logically from the last exhibit. This can be approached through a similar juxtaposition of artifacts and paintings, but it can be more dramatically achieved by showing two period rooms, one the hall of a person of Harwood's stature, and the other the one-room home of a servant. We know that such a house in Martin's Hundred measured only 14' x 12'. Furnishing these rooms would have to rely on a blending of original objects and reproductions, with heavy reliance on the latter. If this course is chosen, the James Anderson style combination of artifact display and antique furnishings might be an effective, if rather costly approach. Yet another might be to build scale models of the rooms to be viewed through peep holes placed at an eye level matching that of a viewer standing within the model. This device helps to give the visitor a far better impression of the model by forcing his eye to adjust to its scale.

- 12We look now at individual household objects, beginning with imported European pottery. This is chosen to lead off for two reasons, 1) it is colorful and attractive, and 2) it brings the visitor back to the "melting pot" theme showing Virginia to have been the recipient not only of people of different nationalities but drawing on the manufactured goods of Holland, France, the German principalities, Spain, Italy, and the Orient. Here again the archaeological fragments will be augmented with details from contemporary genre paintings, and with antiques from the C.W. Department of Collections.

- 13To further dispel the belief that the early Virginia settlers were culturally as well as geographically removed from their European homelands, this next display features ceramics from London (to be loaned by the Museum of London) demonstrating that they are all paralleled among the Carter's Grove discoveries. The background to this case will be drawn from an engraving of a London street in the 1630s, thus giving the modern visitor a glimpse of the kinds of pictures that stayed 9 in the memories of these first generation Virginians. The London exhibit serves also to lead us to the next, enabling the visitor to see that the pottery actually made in Martin's Hundred was as skillfully fashioned as its European prototypes.

- 14

This display shows a range of the local wares (including the now-famous 1631 dish, the earliest dated piece of American pottery), and discusses kiln types and methods of manufacture and pottery-decorating (slip and sgraffito) techniques employed by the local potter.

[We now have good reason to give careful consideration to the possibility of installing an earthenware potter at Carter's Grove, someone sorely missed from our Williamsburg crafts, for the good reason that there was no potter in Williamsburg. Fortunately, the Martin's Hundred pottery includes several shapes that would be readily marketable for modern home use. I would like, therefore, to see such a craft re-established at Martin's Hundred, with the products limited to authentic reproductions that could be sold only at Carter's Grove.]

- 15The next display follows from the last and describes the new spectrographic studies conducted at the College of William and Mary to find a method of distinguishing between pottery made from Virginia clays and those produced elsewhere in America and Europe. This research promises to be a major ceramic development with implications reaching far beyond the immediate field of study. Although the exhibit deals with a scientific project and interrupts the historical theme of the museum, it brings us sharply back to archaeology and reminds the visitor of what it takes to reassemble the pieces of the past.

- 16Continuing the local ceramic story, this exhibit features the ceramic alembic (still top) from Site "A," discussing it not only as a remarkable example of the potter's craft, but also examining its role in the art of distilling. The display will feature contemporary illustrations of distilling equipment and (getting back to Virginia history) will tell something about still-owning Dr. Pott who brewed the poisoned drinks served to Indians on the Potomac by the British negotiating team after the 1622 massacre.

- 17This exhibit covers other household items found in the excavations: glass, cutlery, and kitchen equipment. Special attention is paid to glass bottles (108 of which were represented among the fragments from Site "A") which carries us logically on from the previous discussion of distilling.

- 10

- 18Here follows a display dealing with clothing, represented archaeologically by gold and silver threads, buttons, pins, hooks and eyes, and by buckles of various types. Details from portraits and genre paintings will show how items like these were worn—and by whom.

- 19Next comes a display devoted to tobacco smoking, showing clay pipes both as a l7th-century tool and a 20th-century aid to archaeologists in their efforts to date the ground. The exhibit will outline what we know about the development of the tobacco industry in the early 17th century, a subject which leads us easily into the next display.

- 20Farming: Here, guided by the artifacts, we think about crops and livestock, not so much as exportable commodities but as means of sustaining life in the early, ailing years of colonization. The artifacts will include hoes, spades, axes, part of a saw, and bricks bearing the footprints of turkeys and young pigs. The place of the horse in life at Martin's Hundred (we have two shoes, a stirrup, and part of a gilded spur) may figure in this presentation—although it might equally belong with the military story.

- 21Leading out of the farming exhibit, we turn to enclosures and the evidence we have found of different types of fences. This important feature of l7th-century life will be explained by means of photographs of the archaeological evidence, quotes from contemporary regulations, and details from paintings and woodcuts. All our evidence for domestic fencing comes from Site "A," and therefore the display ends with a model of the layout of the site—which the visitor is about to see on the ground.

- 22

The Site "A" model. This would be treated as an archaeologically excavated site (rather in the style of the model in the Anderson House), but with a painted reconstruction behind it to show what the buildings and enclosures may have looked like in its period of maximum growth. It might be tempting to make the model a reconstruction, but I do not prescribe to that approach for two reasons; 1) I think it important that the visitor should view the layout of the site more or less as he will see it when he gets there, and 2) a reconstruction model tends to give more authority to the details of that reconstruction than we can authenticate. Another alternative is to use dissolving projected overlays which can convert the ground plan into a reconstruction and back again.

11The disadvantage to this is that it can only be viewed through a peep hole, and at this late stage of the museum experience, it would be a mistake to ask the visitors to line up to see something they all need to absorb, but which can only be viewed one at a time.

- 23The visitor has now returned close to his starting point and has an opportunity to look again at the model of the entire plantation before he leaves the building en route to Site "A"—by way of the short woodland trail.

A preliminary scheme included a final display devoted to the few 18th-century discoveries provided by the 1970-71 archaeological study. It was immediately apparent, however, that the total findings were dwarfed by the drama of the 17th- century revelations, and that the injection of the l8th-century story seriously disrupted the flow that leads us from the museum to Site "A." Talking with Roy Graham about this problem, he put forward the good suggestion that there might be other "center" where the l8th-century life of Carter's Grove could be documented both historically and archaeologically, perhaps using the old Superintendent's House as its location. Be that as it may, it is my strong conviction that the Martin's Hundred Museum's great asset is that it is restricted solely to the 17th century, leaving the mansion to dominate the l8th-century narrative.

The Building

The museum building should be a single story structure having a basement area cut into the bank of the ravine to provide space for a utility room, staff rest area, supply and custodial closet, archaeological store and study rooms (for continuing and later work at Carter's Grove), and possibly a screening area for film and slide presentations seating up to fifty people. Clearly there will be a need for a place to show the new film on Carter's Grove archaeology, but as that is designed to run 55 minutes, it is not something that needs to be seen by all visitors, and so may only be screened for special groups. If, however, it becomes apparent (as detailed planning develops) that a short slide presentation would be helpful to all visitors, then the inclusion of a mini-theatre (seating about 35 people) on the gallery floor would be desirable. As any slide presentation of more than three or four minutes' duration seriously disrupts the flow of visitors, a "sit down" screening room is best kept out of the main traffic flow—a factor promoting a lower level location.

The gallery floor should be no more than a well-insulated shell in which the exhibits can be set-up as building blocks under a false ceiling providing maximum lighting flexibility. The kind of winding and varyingly lit course employed (in miniature) at the James Anderson House will be used to give 12 variety to the visitors' progress through the buildings, and to foster the impression that it is larger than it is.

The entrance should be close to the south end of the west wall with the visitor entering directly off the roadway (see Fig. 2). The exit would be at the east end of the south wall leading onto a path running along the edge of the ravine behind the westerly flanking trees, and turning west onto the present service road adjacent to Site "A." Within the building, therefore, the visitor will have progressed in a U, exiting close to where he came in, but emerging into a visually very different environment that allows him to enjoy a brief look at the forest.

There are two reasons for the U-shaped pattern within the building: a) it provides maximum use of space, and b) it enables a small staff to monitor both ends of the exhibition and thus provide better security. One of the principle problems at the Anderson House is that the staff (usually one person) remains tied to the entrance desk and has no knowledge of what is going on at the other end of the building or being sure that people are not entering through the exit. The Martin's Hundred Museum plan reduces that problem, though the inevitable need to keep personnel to a minimum will mean that virtually all exhibits will have to be kept behind glass or protected by security devices.

There should be internal stairs to the basement floor from the foyer, their width dictated by whether or not there would be a theatre below. There would also be a large door at the north end (the closed extremity of the U) to serve both as a service door for the exhibits and as a fire exit. I would hope that, in addition, a service ramp could be laid down behind the building to provide access to the basement storerooms and for wheelchair access to the theatre and rest rooms.

The gallery floor would have windows only in the south (foyer) wall, providing a cheerful entrance and offering a glimpse of the woods through which the departing visitor will later walk. There would, however, be windows along the east wall at the basement level providing light to the staff rest area and workrooms. Needless to say, this rather austere plan makes attractive screen planting along the west wall an essential element of the design.

The plan laid out in Figure 3 is based on the foregoing criteria and shows that such a building and display would be capable of comfortably absorbing about 180 people at a time for a visit of up to forty minutes. However, like the Anderson House exhibit, the story will be told at two paces: fast and measured. Thus, for example, the four-minute Hearphone commentary beside the fort model can be reduced to a twenty-second label. Much of the explanatory caption material will be placed beside the cases, leaving only summarizing labels within, so that the visitor may absorb a little or a lot depending on his interest and time schedule.

13The 120' x 40' building dimension used throughout this proposal is sufficient to house the Martin's Hundred collections so far recovered, i.e. to the close of 1977. Maximum use has been made of case space, but the price of so doing is a very intense, even frenetic museum experience. A somewhat larger building would permit more space between exhibits and thus slow the pace of instruction. It would also enable the number of visitors to be increased and give the architect greater flexibility in creating an attractive as well as functional building.

Equally desirable is a built-in capability to mount additional displays as new finds are recovered from as yet unexcavated Martin's Hundred sites, and as donors come forward with gifts of antiques to parallel the archaeological fragments. Thus, for example, it would be very desirable to have the space to exhibit each of the styles of armor listed in the records as having been imported into Virginia and proven to have been in use in Martin's Hundred by the archaeological discoveries. In addition to a shirt of mail already donated and the half suit of armor I bought while in England, we need a three-quarter suit, a pikeman's cuirass and tassets, a corselet, brigandine, and jack. Together these armors would fill an exhibition space comparable to that now allowed to tell our entire "attack and defense" gallery. Nevertheless, for the purposes of preliminary planning I have restricted the building to the minimum space and the simplest shell.

Funding

The museum and exhibit design are no more than a point of departure—though they have been carried to the degree that if we were to do precisely this, we would have a workable and visitor-pleasing museum. Whether the building will eventually be rectangular, square, or even circular remains to be worked out with the architect; similarly, we are by no means locked into the rather regimented progression I have devised. Nevertheless, we have to start somewhere, and without a fairly well-developed concept it is impossible to demonstrate the scope of the story we have to tell, and, equally importantly, there is no other means of arriving at a preliminary square-foot cost estimate.

The plan (Figure 3), along with another for the basement, have been reviewed by resident architect Roy Graham whose office has provided an estimated cost for the building and the exhibit partitions, cases, and related equipment. It comes to $1,649,774. In providing this estimate, Mr. Graham has allowed for the possibility that substantial modifications to the present plan may be made when the chosen architect reviews it in the light of his own ideas and experience.

It seems to me that we have three and possibly four areas in which friends of Colonial Williamsburg can help us with this exciting project, namely the building and its exhibition construction, an operating endowment, and the donation of objects needed to bring the often fragmentary artifacts to life.

14We have received a notable start to this last element through the generosity of Thomas W. Wood who has given us the shirt of chain mail to match fragments from Sites "B" and "C." Then, too, we have offers of exhibit materials on extended loan from the Tower of London and the Museum of London. I see this help not only as major assets to the exhibits themselves but also as evidence of enthusiasm for the project on the part of two of England's most prestigious museums.

The cost of the Martin's Hundred Museum is, of course, a very different figure to the value of a matchlock musket or a suit of armor, but it provides an opportunity to make a unique contribution to the American public and to American history. It is a project that stand splendidly and visibly alone, one which a donor can truly see as his or her own, rather than being an addition to the Foundation's existing l8th-century programs in Williamsburg and at Carter's Grove.

Dr. Melville B. Grosvenor, chairman emeritus of the National Geographic Society, has told me that he considers the Martin's Hundred discoveries to be the most important contribution to American history that the Society has ever underwritten. I believe that anyone who helps us bring that story to the public will be making no less a contribution, for as I said at the outset, discovery without dissemination is no discovery at all.

I.N.H.

Copy to:

Mr. J. R. Short

Mr. P. A. G. Brown

| Lower Level | |

|---|---|

| Theater—1200 sq. ft. @ $70 | $ 84,000 |

| Reception—1020 sq. ft. @ $70 | 31,400 |

| Staff Room Office—318 sq. ft. @ $50 | 15,900 |

| Archaeology Workroom and Storage—946 sq. ft. @ $35 | 33,110 |

| Utilities—781 sq. ft. @ $50 | 39,050 |

| Toilets—456 sq. ft. @ $45 | 20,520 |

| Circulation, incl. stair—403 sq. ft. @ $50(scaled from drawings) | 20,150 |

| $284,130 | |

| Gross sq. ft. lower level—5124 | |

| First Floor Level | |

| Museum—5124 sq. ft. @ $90 (gross square feet) | 461,160 |

| $745,290 | |

| 10% contingency | 74,529 |

| Total Building Cost | $819,819 |

| Site, road work, parking, and landscaping | $500,000 |

| $1,319,819 | |

| 25% consulting, furnishings, etc. | $329,955 |

| TOTAL PROJECT COST | $1,649,774 |

PROPOSED ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM AT CARTER'S GROVE

Construction Materials

- Lower Level

- Concrete floor slab

- Concrete retaining wall on north, east and west walls

- Waterproof exterior walls below grade.

- Acoustical tile on plaster ceilings.

- First Floor Level

- Concrete slab on bar joists.

- Acoustical tile ceiling.

- Bar joist roof structure with built-up roof.

- Exterior walls to be face brick.

- Heating

- Air Conditioning

- Climate control for protection of artifacts